|

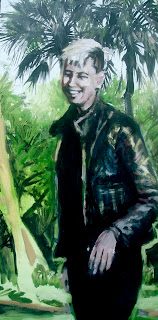

Sergio, harpist

(after a photo by John Schechter)

24" x 12", oil on luan, 2012 |

I

reported a month ago I was working on a CD with examples of weep singing. I have now finished this compilation, it contains 28 tracks and has a 20 page booklet of pictures and explanatory notes. The CD won't be released anywhere but if anyone is interested in this subject or the CD, please write me a note. The texts in this booklet were often pulled from this very blog. Now I'm returning the favor: the following text is from the booklet

Keening Songs and Death Wails. Sergio, the harpist depicted above, is featured on the recording of a Quichuan mother lamenting the death of her 2-year old daughter.

|

Keening Songs and Death Wails

collected by Berry van Boekel

private publication, 2012 |

Quichuan Mother’s Lament (to her 2 year old girl)

Ecuador, January 12-13, 1980, outside Cotacachi, recorded by John Schechter.

In the educational textbook Worlds of Music ethnomusicologist John Schechter gives an account of the circumstances surrounding the recording of this Quichuan’s lament. (Summarizing 4 pages into 1 paragraph): Against a backdrop of a high infant mortality rate amongst Catholicized Quichua Indians in Ecuador a wake is organized for the passing of a two year old girl. The wake is festive, there’s food, drink, music, and dance. The musician is harpist Sergio, he plays non stop local favorite (traditional) dance music. The girl is put on the floor, decorated with the finest adornments, and just before her casket is closed, laid on a higher table, and a ladder put against it (to symbolize the ascension to a higher realm) her mother sings a song. The song is improvised, the lyrics almost impossible to decipher because of the mother’s sobbing, halfway into the song Sergio starts playing the harp again, and the song becomes different, more joyful.

|

Gustave Doré: A festive child’s wake

in the Spanish Mediterranean, 1870s |

In many Latin American countries the passing of an infant is a festive occasion. When an infant died he/she is sinless and becomes an angle. The child did not have to endure the impurities and hardships of life adults have. In 1980, when the account by Schlechter was written, the mortality rate of infants was three out of ten. Funerary lamentation is a widespread practice among catholic countries/regions. It is said to have originated in Roman times but the origins of the singing at wakes and funerals may well go further back than Christianity does. A lamentation is an improvisation of an unaccompanied female wailing voice. The singer is often a relative of the deceased but also could be a hired professional "wailing" woman. In Ireland she's called a "keener", in Romania a "bocitorre", and in Corsica "voceratrice". Laments can be divided up into two categories: that of the wakes and funerals for adults, and for those of children. The adult ones are mournful while children's laments can have a festive quality to them as it is celebrated when a child "becomes an angel" without having experienced the hardships and impurities of life. The practice has become nearly extinct now but it used to be a tradition in nearly all catholic societies. It could be found throughout the Mediterranean, Latin America, Eastern Europe, and other pockets of Catholicism that existed around the globe. I grew up in the Catholic Netherlands, but I don't think lamentation was ever practiced there. It certainly wasn't when my grandparents died while I was still a little boy in the late 1960s. The Netherlands had a sober kind of Catholicism, it had the introverted ascetic characteristics of it but not not the extroverted spirituality. The folk music in Mediterranean and Latin American countries were influenced by a rich spirituality and a cult of the death.

Source:

Worlds of Music: An Introduction to the Music of the World's People, 4th ed., Jeff Todd Titon (ed.), Schirmer, 2002